Greece's Gospel Riots of 1901: Language, Faith, and the Firestorm over a Translation

It starts with a queen reading to wounded soldiers. After Greece's defeat in the 1897 war, Queen Olga of Greece, Russian-born and compassionate, sits by hospital beds, reading the Bible to comfort injured men. But she notices something that shocks her: the soldiers can't understand the scriptures.

They call it "deep Greek for the learned." The archaic language of the Church is incomprehensible to ordinary Greeks. Moved by this realization, Queen Olga makes a decision that will change Greek history: she commissions a translation of the Gospels into the language "we all speak": Demotic Greek.

Her translation is published in 1898. Surprisingly, it's met with quiet acceptance. The books sell steadily. For a moment, it seems the controversy might pass.

Queen Olga of Greece, whose compassion for wounded soldiers led her to commission a translation that would spark one of Greece's most violent language debates.

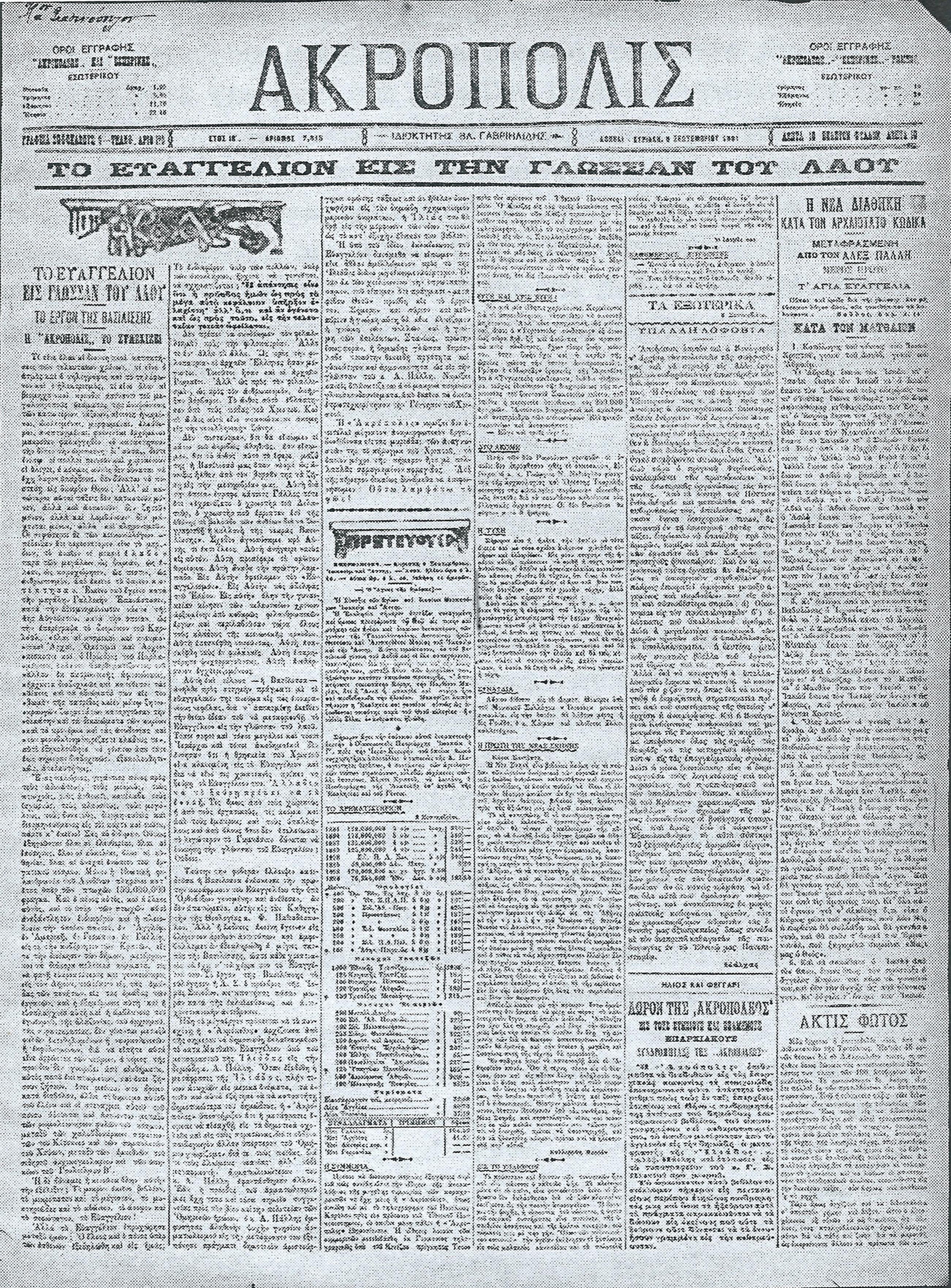

The Akropolis newspaper front page from September 1901 that ignited the riots with its bold headline: "THE GOSPEL IN THE LANGUAGE OF THE PEOPLE."

Then, in September 1901, a journalist named Alexandros Pallis takes up the cause. He begins serializing his own Gospel translation in the progressive newspaper Akropolis, with a bold front-page headline: "THE GOSPEL IN THE LANGUAGE OF THE PEOPLE."

The editorial invokes Christmas imagery: "as though one is hearing the bells that first greeted the Birth of Christ." But those gentle bells would soon be drowned out by the roar of riots.

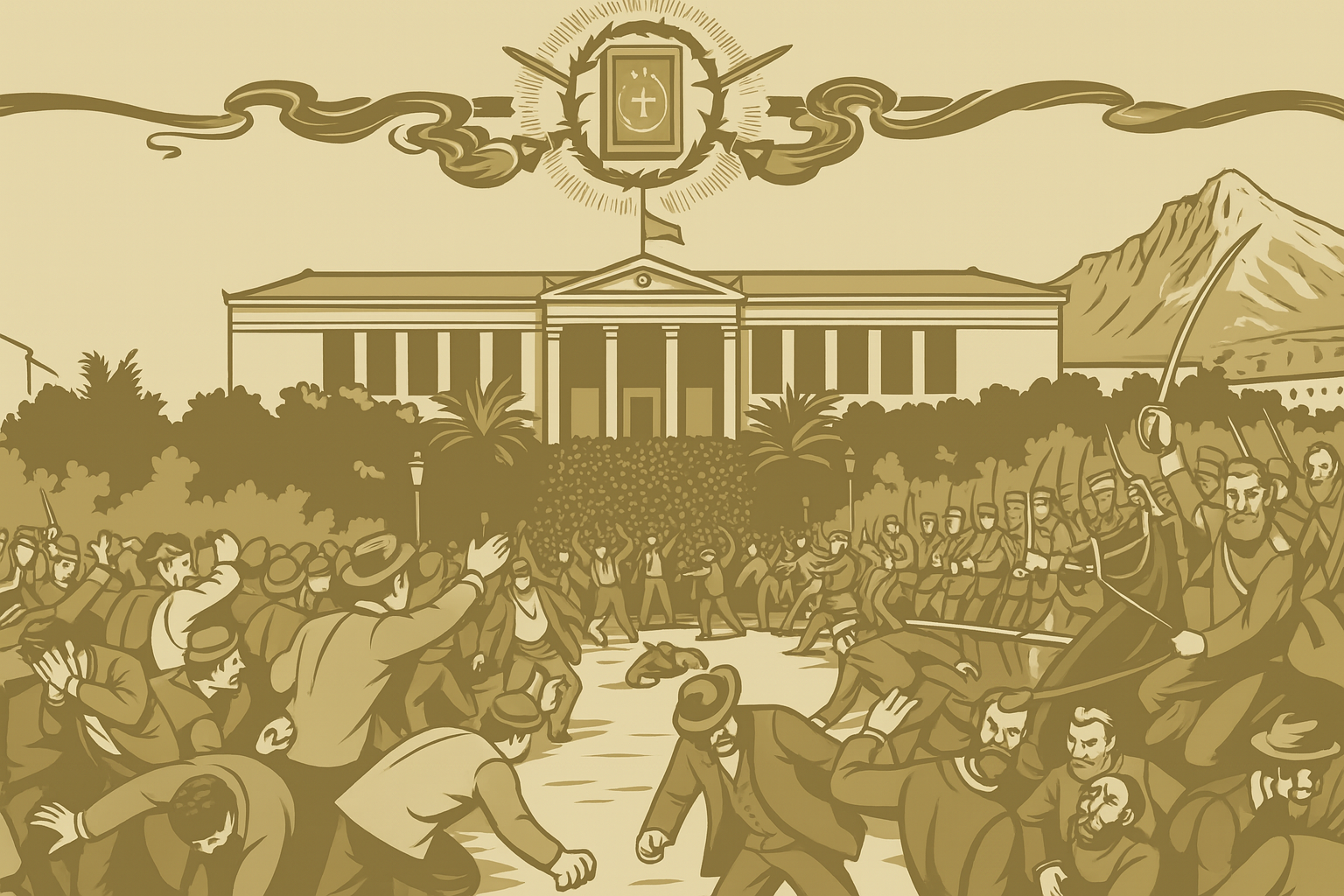

By November 8, 1901, "Black Thursday," 10,000 protesters fill the streets of Athens. Shots ring out. Cavalry charges with sabers. When the smoke clears, eight people lie dead on the blood-stained streets. The government falls. The Church bans all modern Greek Bible translations for 84 years.

This is the Gospel Riots of 1901. And 125 years later, it still shapes how Greeks celebrate Christmas, how they read their Bibles, and how they think about their own language.

The language war that killed people

To understand why translating a Christmas story caused deaths, you need to understand Greece's language question: a debate that divided the country for over a century.

Greece at the turn of the 20th century existed in a state of diglossia: effectively two languages coexisting:

Katharevousa ("purified" Greek): An artificial, archaic form created in the 1800s to "purify" Greek by removing foreign influences. It mimicked Ancient Greek grammar and vocabulary. It was the language of government, education, and the Church. After winning independence in the 19th century, the new Greek state clung to an idealized past where Ancient Greek was the gold standard of culture. The educated elite promoted Katharevousa to reconnect the nation with its classical glory.

Demotic Greek: The living language Greeks actually spoke at home, in markets, with their families. It had evolved naturally over 2,000 years, absorbing words from Turkish, Italian, and other languages, shaped by centuries of change, including influences from Ottoman rule.

The Church and traditionalists saw Demotic as "corrupted" and "vulgar." The powerful Holy Synod of the Greek Orthodox Church refused to approve any modern Greek translation, arguing that the Church "had never approved the translation of Holy Scriptures into a vulgar and base language."

But the opposition wasn't just religious zealotry. It was fueled by a deeper fear: if Greeks admitted their Bible needed translating, were they admitting they were different from their revered ancestors? Conservative nationalists feared it would weaken Greece's claim to be the true heir of Byzantium and classical Hellas, perhaps even encouraging separatist sentiments among non-Greek speakers in the kingdom.

When Pallis published his translation, he wasn't just translating words. He was challenging who gets to control the sacred text and threatening the very foundation of Greek national identity.

November 8, 1901: Black Thursday, the day Athens burned

The reaction to Pallis's serialization was immediate and explosive. Conservative newspapers, university professors, and clergy united in outrage. "Blasphemy!" "Sacrilege!" cried students of Athens University as they formed angry mobs.

The establishment press and the Holy Synod fumed that the new translation was "vulgar" and "degrading" to Scripture. Pamphlets and editorials demonized Pallis as a national traitor, "an agent of Pan-Slavism," and a "sleazy... evil creature" conspiring with the long-haired liberal "malliaroi" ("hairy ones") to undermine the Greek language and nation. Some even suggested this was a foreign Protestant plot. After all, Pallis had lived in Britain, and the push to put vernacular Bibles in everyone's hands smelled of Protestant missionary influence to Orthodox eyes.

Monday, November 4: Student demonstrators storm the offices of Akropolis, burning stacks of newspapers that contained the offending Gospel installment. Shouting "Down with the blasphemers!" they attack another pro-translation newspaper, then march to the residence of Metropolitan Prokopios of Athens, the very clergyman who had privately supported the Queen's translation. Caught in an impossible position, Prokopios tries to appease the crowd, assuring them he too opposes "sacrilegious" translations.

Tuesday, November 5: Thousands of protesters, now swelled by outraged citizens, rally in Athens. They march on the royal palace demanding to see the King, only to be rebuffed by guards. Street clashes intensify. Demonstrators occupy the university in a tense sit-in. Slogans ring out in ancient Greek phrasing, calling for excommunications of the translators: "Anathema! Excommunicate them!"

Thursday, November 8, "Black Thursday": The showdown reaches its tragic climax. By now, some 10,000 Athenians are thronging the streets. The government, fearing revolution, has summoned military reinforcements. Under pouring autumn rain, demonstrators and soldiers eye each other in a standoff around the University and Cathedral.

Suddenly, a scuffle at the front: someone in the crowd fires a gun at the lines of cavalry. Shots erupt in both directions, and chaos descends. Mounted troopers charge with sabers, and volleys of gunfire send people screaming. In the melee, Prime Minister Georgios Theotokis himself narrowly escapes a bullet as he tries to calm the situation.

When the smoke clears and the crowds finally scatter, eight protesters lie dead and dozens are injured on the blood-stained streets of Athens. What had begun as a debate over words had led to very real and tragic bloodshed.

The immediate aftermath:

- Prime Minister Theotokis resigns on November 11, 1901, blamed for mishandling the crisis

- Metropolitan Prokopios is forced to resign his post as Athens' metropolitan bishop. The very man who had tried to bridge the divide between ancient scripture and modern souls becomes a scapegoat

- Starting November 25, 1901, the Orthodox Holy Synod declares any translation of the Bible into common Greek strictly forbidden

- Churches across the country read out a decree banning on pain of excommunication the sale or reading of any modern Greek Gospels

- All existing copies of such translations are ordered confiscated and removed from circulation

- The Church forbids the employment of any teachers known to support the demotic language movement, not only in Greece but in Greek communities abroad in the Ottoman Empire

The ban lasted until 1985, 84 years later.

Why this still matters at Christmas

Every December, Greeks sing Kalanta (Christmas carols). Many of these carols use archaic, formal language that sounds beautiful but isn't how Greeks actually speak today. This isn't an accident. It's a legacy of the language war.

Greek children singing Kalanta (Christmas carols), many of which still use the formal, archaic language that became standard after the Gospel Riots.

The irony is profound: The Gospels of Matthew and Luke contain the Nativity story: the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, heralded by angels and humble shepherds. Those events are commemorated every year in churches throughout Greece, typically in the ancient liturgical language. Queen Olga and Alexandros Pallis wanted to bring that same Christmas story of hope to people in a language they could feel in their hearts.

In fact, the Akropolis editorial that sparked the riots invoked the gentle image of bell sounds carrying over distant hills at Christ's birth, a scene of pastoral peace. It's heartbreaking that such a message of comfort led to street battles.

The Church's 84-year ban on Demotic translations meant that:

- Religious texts stayed in archaic Greek, creating a gap between everyday language and sacred language

- Christmas traditions became formalized: carols, prayers, and readings used the "purified" form

- A generation grew up feeling that "real" Greek was the formal version, not what they spoke at home

- The Christmas story became inaccessible: the very message meant for everyone was locked in a language few could fully understand

Even today, many Greeks feel their everyday language is "less Greek" than the formal version. That feeling comes from 1901.

The controversial question: Should Christmas be in "pure" Greek?

This debate never fully ended. It just moved underground.

Traditionalists argue:

- Sacred texts deserve "pure" language

- Archaic Greek connects modern Greeks to their ancient heritage

- Formal language elevates the religious experience

Modernists counter:

- If people can't understand it, what's the point?

- Language evolves. That's natural, not corruption

- The Gospel Riots proved that language control is about power, not piety

The middle ground: Many Greeks today use both. They sing formal carols at church but tell the Christmas story to their children in everyday Greek. They read the Bible in Katharevousa for tradition but discuss it in Demotic for understanding.

But the tension remains. Every Christmas, Greeks navigate this linguistic divide, often without realizing it's a 125-year-old battle.

What's your view on the Greek language debate?

The lesson: Language is power

The Gospel Riots weren't really about translation. They were about who controls meaning.

When you control the language of sacred texts, you control:

- Who can access them

- How they're interpreted

- What counts as "authentic" Greek identity

The rioters weren't just protecting tradition. They were protecting a system where only educated elites could fully understand religious texts, and therefore, only they could interpret them.

The events of 1901 entrenched a bitter antagonism between the Orthodox Church and proponents of language reform. For decades to come, any attempt to elevate demotic Greek faced staunch resistance. Schools stuck to the archaic forms; writers who dared use demotic were marginalized. In a very real sense, 1901 froze progress on the "language question" in Greece for a generation.

The idea that "the language of the people" could stand alongside the language of the ancients had become, to conservatives, synonymous with treason and impiety.

Sound familiar? This pattern repeats across languages and cultures. The "pure" form vs. the "corrupted" form. The "correct" way vs. the "vulgar" way. The "authentic" vs. the "modern."

Yet the pendulum of history would slowly swing. Reforms in the 1910s and 1920s (under leaders like Eleftherios Venizelos) cautiously introduced demotic Greek in education and public life. Ultimately, many years later, in 1976, demotic Greek was finally declared the official language of Greece, a victory for the very idea that had once incited riots.

The real Christmas story: A lesson in irony

The irony is profound on multiple levels. The original Christmas story was told in Koine Greek, the everyday language of ordinary people in the 1st century, not the formal Classical Greek of scholars.

Jesus's birth was announced to shepherds, not professors. The wise men came from the East, not from Athens. The story was meant to be understood by everyone.

But there's a deeper irony: The Gospels, which proclaim "peace on earth, goodwill toward men," became the source of violence on the streets of Christian Athens. The very season that celebrates the Word becoming flesh (in Christian belief) saw Greeks of 1901 fighting over words.

Maybe that's the real lesson of the Gospel Riots: When you make a story too formal, too pure, too controlled, you risk losing what made it powerful in the first place.

The story of a child born in a stable, announced to ordinary people, meant for everyone.

Even if they speak "vulgar" Greek.

Christmas 2025: From riots to reflection

Today, Greek churches do allow scripture readings in modern Greek alongside the ancient texts. Greek society long ago accepted that loving your language can mean letting it grow. The violence is gone. But the question remains: Who gets to decide what Greek is?

As we celebrate Christmas, the tale of the Gospel Riots serves as a reminder that peace on earth often begins with understanding each other's language, literally and figuratively. It's a story rich with drama and lessons.

Language learners can take heart that the struggle to understand and be understood is as old as history, and sometimes, as this story shows, making meaning accessible is a courageous act. This Christmas, in the spirit of the season, we can appreciate that we have the freedom to read cherished stories in our own tongue, a hard-won gift from those who dared to bring words to the people.

Peace on earth, goodwill to all, in every language.

Want to learn Greek that actually works?

The language war taught us one thing: Real communication matters more than linguistic purity.

At Fluoverse, we help you learn Greek (and other languages) through real conversations: the kind you'll actually have, not the kind that would have made 1901 Athens riot.

Because the best language is the one people understand.

💜💙 Fluoverse: Empowering every language learner to speak with confidence. 💜💙